On Benchmarking, Part 5

04 Feb 2017This is a long series of posts where I try to teach myself how to run rigorous, reproducible microbenchmarks on Linux. You may want to start from the first one and learn with me as I go along. I am certain to make mistakes, please write be back in this bug when I do.

In my previous post I convinced myself that the data we are dealing with does not fit the most common distributions such as normal, exponential or lognormal, and therefore I decided to use nonparametric statistics to analyze the data. I also used power analysis to determine the number of samples necessary to have high confidence in the results.

In this post I will choose the statistical test of hypothesis, and verify that the assumptions for the test hold. I will also familiarize myself with the test by using some mock data. This will address two of the issues raised in Part 1 of this series. Specifically [I10]: the lack of statistical significance in the results, in other words, whether they can be explained by luck alone or not, and [I11]: justifying how I select the statistic to measure the effect.

Modeling the Problem

I need to turn the original problem into the language of statistics,

if the reader recalls, I want to compare the performance of two

classes in JayBeams:

array_based_order_book against

map_based_order_book,

and determine if they are really different or the results can be

explained by luck.

I am going to model the performance results as random variables,

I will use for the performance results (the running time of the

benchmark) of array_based_order_book and for

map_based_order_book.

If all we wanted to compare was the mean of these random variables I could use Student’s t-test. While the underlying distributions are not normal, the test only requires [1] that the statistic you compare follows the normal distribution. The (difference of)means most likely distributes normal for large samples, as the CLT applies in a wide range of circumstances.

But I have convinced myself, and hopefully the reader, that the mean is not a great statistic for this type of data. It is not a robust statistic, and outliers should be common because of the long tail in the data. I would prefer a more robust test.

The Mann-Whitney U Test is often recommended when the underlying distributions are not normal. It can be used to test the hypothesis that

which is exactly what I am looking for.

I want to assert that it is more likely that array_based_order_book

will run faster than map_based_order_book.

I do not need to assert that it is always faster, just that it is a

good bet that it is.

The Mann-Whitney U test also requires me to make a relatively weak set

of assumptions, which I will check next.

Assumption: The responses are ordinal This is trivial, the responses are real numbers that can be readily sorted.

Assumption: Null Hypothesis is of the right form I define the null hypothesis to match the requirements of the test:

Intuitively this definition is saying that the code changes had no effect, that both versions have the same probability of being faster than the other.

Assumption: Alternative Hypothesis is of the right form I define the alternative hypothesis to match the assumptions of the test:

Notice that this is weaker than what I would like to assert:

As we will see in the Appendix that alternative hypothesis requires additional assumptions that I cannot make, specifically that the two distributions only differ by some location parameter.

Assumption: Random Samples from Populations The test assumes the samples are random and extracted from a single population. It would be really bad, for example, if I grabbed half my samples from one population and half from another, that would break the “identically distributed” assumption that almost any statistical procedure requires. It would also be a “Bad Thing”[tm] if my samples were biased in any way.

I think the issue of sampling from a single population is trivial, by definition we are extracting samples from one population. I have already discussed the problems in biasing that my approach has. while not perfect, I believe it to be good enough for the time being, and will proceed under the assumption that no biases exist.

Assumption: All the observations are independent of each other I left the more difficult one for last. This is a non-trivial assumption in my case because one can reasonably argue that result of one experiment may affect the results of the next one. Running the benchmark populates the instruction and data cache, affects the state of the memory arena, and may change the P-state of the CPU. Furthermore, the samples are generated using a PRNG, if the generator was chosen poorly the samples may be auto-correlated.

So I need to perform at least a basic test for independence of the samples.

Checking Independence

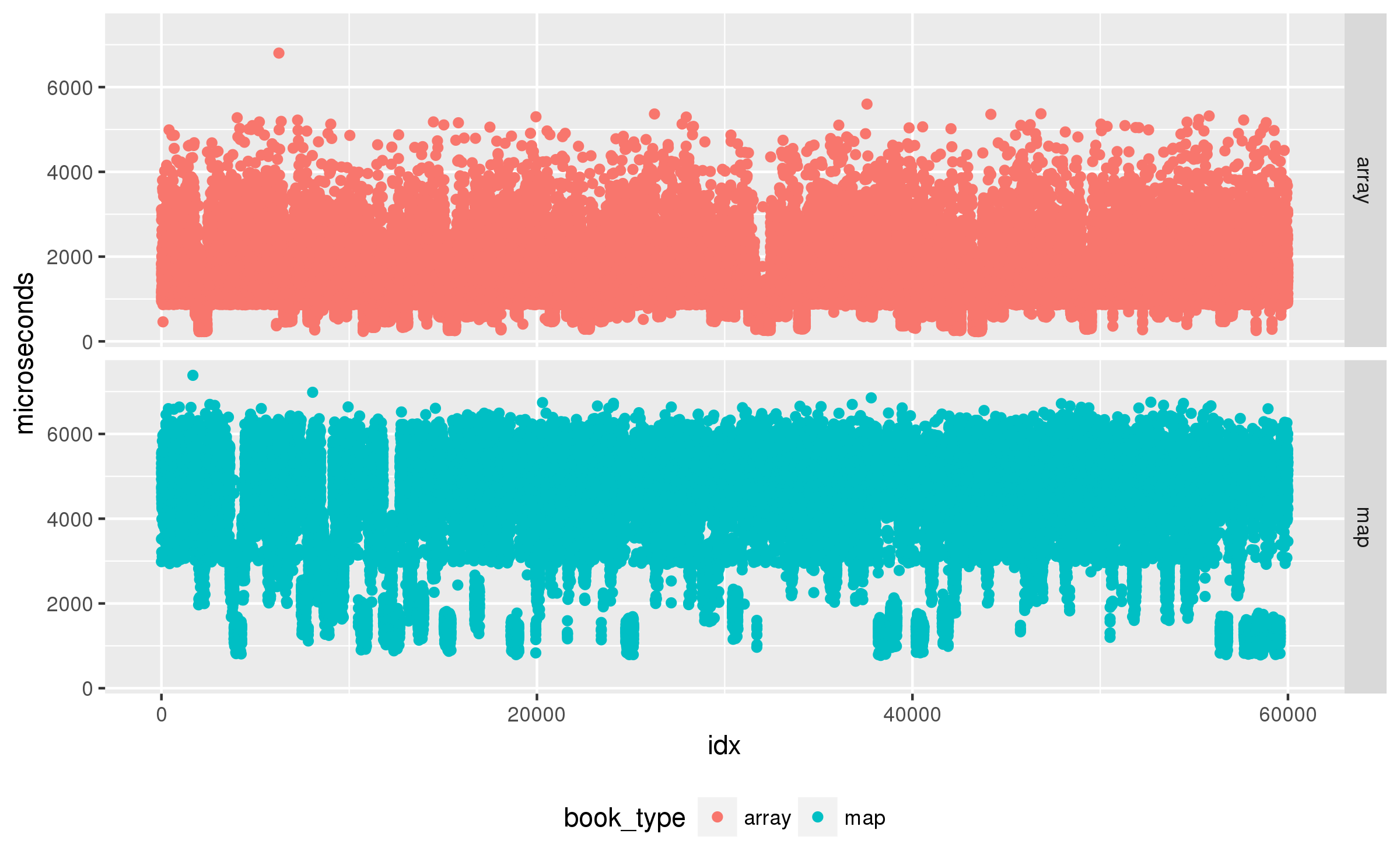

To check independence I first plot the raw results:

Uh oh, those drops and peaks are not single points, there seems to be periods of time when the test runs faster or slower. That does not bode well for an independence test. I will use a correlogram to examine if the data shows any auto-correlation:

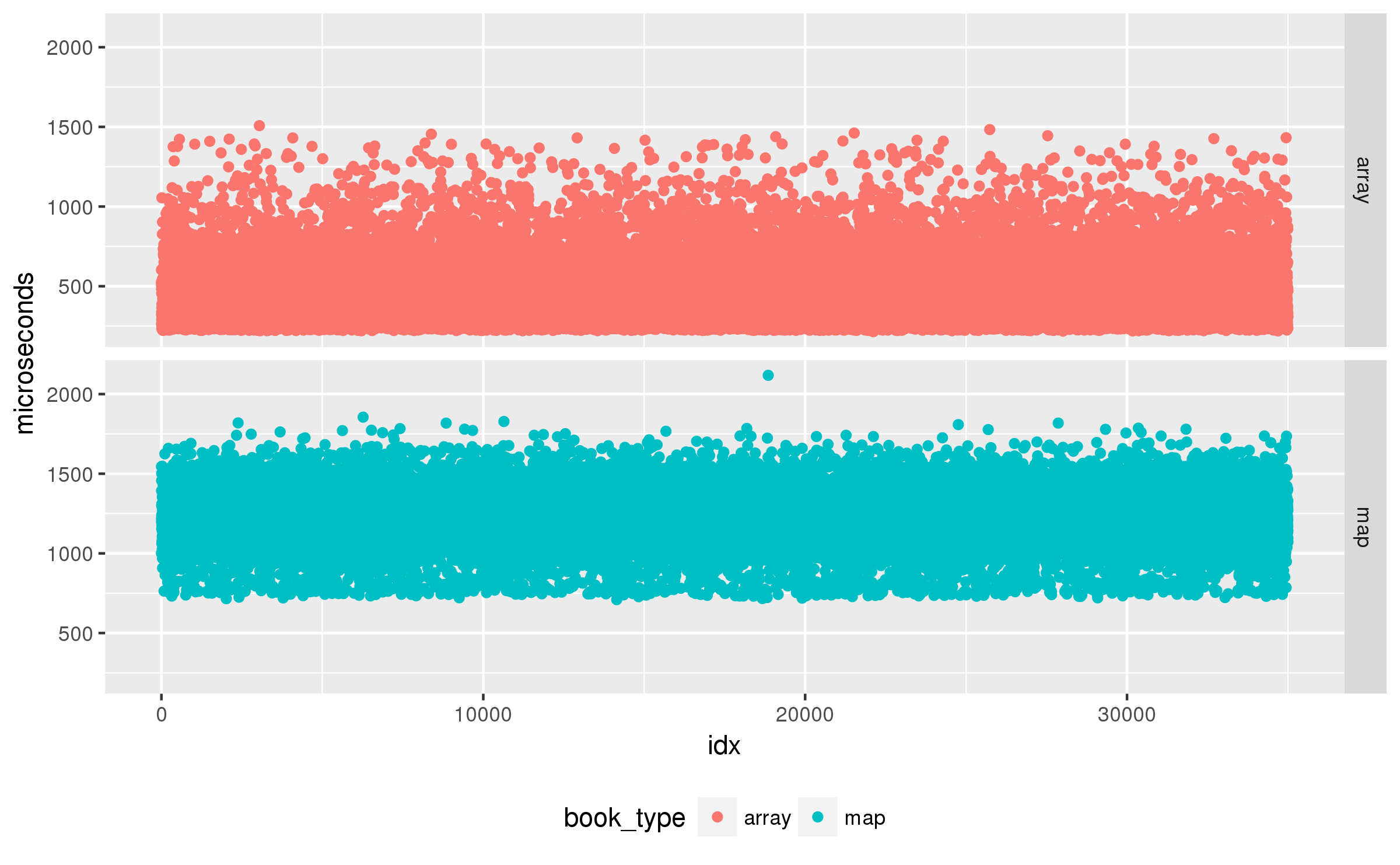

That is a lot of auto-correlation. What is wrong? After a long chase suspecting my random number generators I finally identified the bug I had accidentally disabled the CPU frequency scaling settings in the benchmark driver. The data is auto-correlated because sometimes the load generated by the benchmark changes the P-state of the processor, and that affects several future results. A quick fix to set the P-state to a fixed value, and the results look much better:

Other than the trivial autocorrelation at lag 0, the maximum autocorrelation for map and array is , that seems acceptably low to me.

Measuring the Effect

I have not yet declared how we are going to measure the effect. The standard statistic to use in conjunction with Mann-Whitney U test is the Hodges-Lehmann Estimator. Its definition is relatively simple: take all the pairs formed by taking one sample from and one sample from , compute the differences of each pair, then compute the median of those differences, that is the value of the estimator.

Intuitively, if is the value of the Hodges-Lehmann estimator then we can say that at least 50% of the time

and – if is negative – then at least 50% of the time the

array_based_order_book is faster than map_based_order_book.

I have to be careful, because I cannot make assertions about all of

the time. It is possible that the p51 of those differences of pairs

is a large positive number, and we will see in the

Appendix that

such results are quite possible.

Applying the Test

Applying the statistical test is a bit of an anti-climax. But let’s recall what we are about to do:

- The results are only interesting if the effect, as measured by the Hodges-Lehmann Estimator is larger than the minimum desired effect, which I set to in a previous post.

- The test needs at least 35,000 iterations to be sufficiently powered () to detect that effect at a significance level of , as long as the estimated standard deviation is less than .

- We are going to use the Mann-Whitney U test to test the null hypothesis that both distributions are identical.

data.hl <- HodgesLehmann(

x=subset(data, book_type=='array')$microseconds,

y=subset(data, book_type=='map')$microseconds,

conf.level=0.95)

print(data.hl)

est lwr.ci upr.ci

-816.907 -819.243 -814.566

The estimated effect is, therefore, at least . We verify that the estimated standard deviations are small enough to keep the test sufficiently powered:

require(boot)

data.array.sd.boot <- boot(data=subset(

data, book_type=='array')$microseconds, R=10000,

statistic=function(d, i) sd(d[i]))

data.array.sd.ci <- boot.ci(

data.array.sd.boot, type=c('perc', 'norm', 'basic'))

print(data.array.sd.ci)

BOOTSTRAP CONFIDENCE INTERVAL CALCULATIONS

Based on 10000 bootstrap replicates

CALL :

boot.ci(boot.out = data.array.sd.boot, type = c("perc", "norm",

"basic"))

Intervals :

Level Normal Basic Percentile

95% (185.1, 189.5 ) (185.1, 189.5 ) (185.1, 189.5 )

Calculations and Intervals on Original Scale

data.map.sd.boot <- boot(data=subset(

data, book_type=='map')$microseconds, R=10000,

statistic=function(d, i) sd(d[i]))

data.map.sd.ci <- boot.ci(

data.map.sd.boot, type=c('perc', 'norm', 'basic'))

print(data.map.sd.ci)

BOOTSTRAP CONFIDENCE INTERVAL CALCULATIONS

Based on 10000 bootstrap replicates

CALL :

boot.ci(boot.out = data.map.sd.boot, type = c("perc", "norm", "basic"))

Intervals :

Level Normal Basic Percentile

95% (154.6, 157.1 ) (154.6, 157.1 ) (154.6, 157.1 )

Calculations and Intervals on Original Scale

So all assumptions are met to run the hypothesis test.

R calls this test wilcox.test() because there is no general

agreement on the literature about whether “Mann-Whitney U test” or

“Wilcoxon Rank Sum” is the correct name, regardless, running the test

is easy:

data.mw <- wilcox.test(microseconds ~ book_type, data=data)

print(data.mw)

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

data: microseconds by book_type

W = 7902700, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

Therefore we can reject the null hypothesis that

at the confidence level.

Summary

I have addressed one of the remaining issues from the first post in the series:

-

[I10] I have provided a comparison of the performance of

array_based_order_bookagainstmap_based_order_book, based on the Mann-Whitney U test, and shown that these results are very likely not explained by luck alone. I verified that the problem matches the necessary assumptions of the Mann-Whitney U test, and found a bug in my test framework in the process. -

[I11] I used the Hodges-Lehmann estimator to measure the effect, mostly because it is the recommended estimator for the Mann-Whitney U test. In an Appendix I show how this estimator is better than the difference of means and the difference of medians for this type of data.

Next Up

In the next post I would like to show how to completely automate the executions of such benchmarks, and make it possible to any reader to run the tests themselves.

Appendix: Familiarizing with the Mann-Whitney Test

I find it useful to test new statistical tools with fake data to familiarize myself with them. I also think it is useful to gain some understand of what the results should be in ideal conditions, so we can interpret the results of live conditions better.

The trivial test

I asked R to generate some random samples for me, fitting the Lognormal distribution. I picked Lognormal because, if you squint really hard, it looks vaguely like latency data:

lnorm.s1 <- rlnorm(50000, 5, 0.2)

qplot(x=lnorm.s1, geom="density", color=factor("s1"))

I always try to see what a statistical test says when I feed it identical data on both sides. One should expect the test to fail to reject the null hypothesis in this case, because the null hypothesis is that both sets are the same. If you find the language of statistical testing somewhat convoluted (e.g. “fail to reject” instead of simple “accept”), you are not alone, I think that is the sad cost of rigor.

s1.w <- wilcox.test(x=lnorm.s1, lnorm.s1, conf.int=TRUE)

print(s1.w)

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

data: lnorm.s1 and lnorm.s1

W = 1.25e+09, p-value = 1

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-0.3711732 0.3711731

sample estimates:

difference in location

-6.243272e-08

That seems like a reasonable answer, the p-value is about as high as it can get, and the estimate of the location parameter difference is close to 0.

Two Samples from the same Distribution

I next try with a second sample from the same distribution, the test should fail to reject the null again, and the estimate should be close to 0:

lnorm.s2 <- rlnorm(50000, 5, 0.2)

require(reshape2)

df <- melt(data.frame(s1=lnorm.s1, s2=lnorm.s2))

colnames(df) <- c('sample', 'value')

ggplot(data=df, aes(x=value, color=sample)) + geom_density()

w.s1.s2 <- wilcox.test(x=lnorm.s1, y=lnorm.s2, conf.int=TRUE)

print(w.s1.s2)

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

data: lnorm.s1 and lnorm.s2

W = 1252400000, p-value = 0.5975

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-0.2713750 0.4712574

sample estimates:

difference in location

0.09992599

That seems like a good answer too. Conventionally the one fails to reject the null if the p-value is above 0.01 or 0.05. The output of the test is telling us that under the null hypothesis one would obtain this result (or something more extreme) of the time. That seems pretty good odds to reject the null indeed. Notice that the estimate for the location parameter difference is not zero (which we know to be the true value), but the confidence interval does include 0.

Statistical Power Revisited

Okay, so this test seems to give sensible answers when we give it data from identical distributions. What I want to do is try it with different distributions, let’s start with something super simple: two distributions that are slightly shifted from each other:

lnorm.s3 <- 4000.0 + rlnorm(50000, 5, 0.2)

lnorm.s4 <- 4000.1 + rlnorm(50000, 5, 0.2)

df <- melt(data.frame(s3=lnorm.s3, s4=lnorm.s4))

colnames(df) <- c('sample', 'value')

ggplot(data=df, aes(x=value, color=sample)) + geom_density()

We can use the Mann-Whitney test to compare them:

w.s3.s4 <- wilcox.test(x=lnorm.s3, y=lnorm.s4, conf.int=TRUE)

print(w.s3.s4)

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

data: lnorm.s3 and lnorm.s4

W = 1249300000, p-value = 0.8718

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-0.4038061 0.3425407

sample estimates:

difference in location

-0.03069523

Hmmm… Ideally we would have rejected the null in this case, but we cannot (p-value is higher than my typical 0.01 significance level). What is going on? And why does the 95% confidence interval for the estimate includes 0? We know the difference is 0.1. I “forgot” to do power analysis again. This test is not sufficiently powered:

require(pwr)

print(power.t.test(delta=0.1, sd=sd(lnorm.s3), sig.level=0.05, power=0.8))

Two-sample t test power calculation

n = 1486639

delta = 0.1

sd = 30.77399

sig.level = 0.05

power = 0.8

alternative = two.sided

NOTE: n is number in *each* group

Ugh, we would need about 1.5 million samples to reliably detect an effect the size of our small 0.1 shift. How much can we detect with about 50,000 samples?

print(power.t.test(n=50000, delta=NULL, sd=sd(lnorm.s3),

sig.level=0.05, power=0.8))

Two-sample t test power calculation

n = 50000

delta = 0.5452834

sd = 30.77399

sig.level = 0.05

power = 0.8

alternative = two.sided

NOTE: n is number in *each* group

Seems like we need to either pick larger effects, or larger sample sizes.

A Sufficiently Powered Test

I am going to pick larger effects, anything higher than 0.54 would work, let’s use 1.0 because that is easy to type:

lnorm.s5 <- 4000 + rlnorm(50000, 5, 0.2)

lnorm.s6 <- 4001 + rlnorm(50000, 5, 0.2)

df <- melt(data.frame(s5=lnorm.s5, s6=lnorm.s6))

colnames(df) <- c('sample', 'value')

ggplot(data=df, aes(x=value, color=sample)) + geom_density()

s5.s6.w <- wilcox.test(x=lnorm.s5, y=lnorm.s6, conf.int=TRUE)

print(s5.s6.w)

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

data: lnorm.s5 and lnorm.s6

W = 1220100000, p-value = 5.454e-11

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-1.6227139 -0.8759441

sample estimates:

difference in location

-1.249286

It is working again! Now I can reject the null hypothesis at the

0.01 level (p-value is much smaller than that).

The effect estimate is -1.24, and we know the test is powered enough

to detect that.

We also know (now) that the test basically estimates the location

parameter of the x series against the second series.

Better Accuracy for the Test

The parameter estimate is not very accurate though, the true parameter is -1.0, we got -1.24. Yes, the true value falls in the 95% confidence interval, but how can we make that interval smaller? We can either increase the number of samples or the effect, let’s go with the effect:

lnorm.s7 <- 4000 + rlnorm(50000, 5, 0.2)

lnorm.s8 <- 4005 + rlnorm(50000, 5, 0.2)

df <- melt(data.frame(s7=lnorm.s7, s8=lnorm.s8))

colnames(df) <- c('sample', 'value')

ggplot(data=df, aes(x=value, color=sample)) + geom_density()

s7.s8.w <- wilcox.test(x=lnorm.s7, y=lnorm.s8, conf.int=TRUE)

print(s7.s8.w)

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

data: lnorm.s7 and lnorm.s8

W = 1136100000, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-5.110127 -4.367495

sample estimates:

difference in location

-4.738913

I think the lesson here is that for better estimates of the parameter you need to have a sample count much higher than the minimum required to detect that effect size.

Testing with Mixed Distributions

So far we have been using a very simple Lognormal distribution, I know the test data is more difficult than this, I rejected a number of standard distributions in the previous post.

First we create a function to generate random samples from a mix of distributions:

rmixed <- function(n, shape=0.2, scale=2000) {

g1 <- rlnorm(0.7*n, sdlog=shape)

g2 <- 1.0 + rlnorm(0.2*n, sdlog=shape)

g3 <- 3.0 + rlnorm(0.1*n, sdlog=shape)

v <- scale * append(append(g1, g2), g3)

## Generate a random permutation, otherwise g1, g2, and g3 are in

## order in the vector

return(sample(v))

}

And then we select a few samples using that distribution:

mixed.test <- 1000 + rmixed(20000)

qplot(x=mixed.test, color=factor("mixed.test"), geom="density")

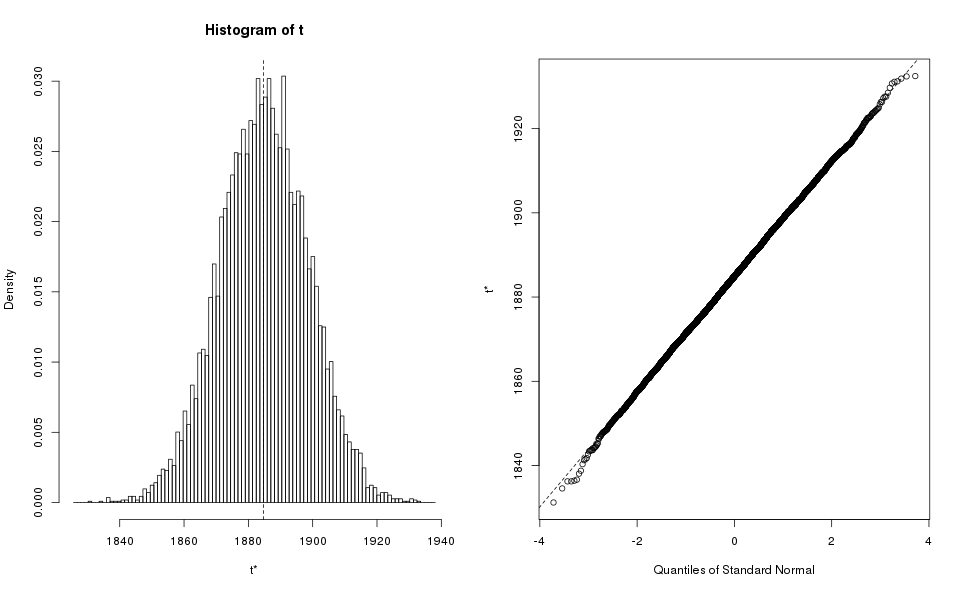

That is more interesting, admittedly not as difficult as the distribution from our benchmarks, but at least not trivial. I would like to know how many samples to take to measure an effect of , which requires computing the standard deviation of the mixed distribution. I use bootstrapping to obtain an estimate:

require(boot)

mixed.boot <- boot(data=mixed.test, R=10000,

statistic=function(d, i) sd(d[i]))

plot(mixed.boot)

That seems like a good bootstrap graph, so we can proceed to get the bootstrap value:

mixed.ci <- boot.ci(mixed.boot, type=c('perc', 'norm', 'basic'))

print(mixed.ci)

BOOTSTRAP CONFIDENCE INTERVAL CALCULATIONS

Based on 10000 bootstrap replicates

CALL :

boot.ci(boot.out = mixed.boot, type = c("perc", "norm", "basic"))

Intervals :

Level Normal Basic Percentile

95% (1858, 1911 ) (1858, 1911 ) (1858, 1912 )

Calculations and Intervals on Original Scale

That seems pretty consistent too, so I can take the worst case as my estimate:

mixed.sd <- ceiling(max(mixed.ci$normal[[3]], mixed.ci$basic[[4]],

mixed.ci$percent[[4]]))

print(mixed.sd)

[1] 1912

Power analysis for the Mixed Distributions

With the estimated standard deviation out of the way, I can compute the required number of samples to achieve a certain power and significance level. I am picking 0.95 and 0.01, respectively:

mixed.pw <- power.t.test(delta=50, sd=mixed.sd, sig.level=0.01, power=0.95)

print(mixed.pw)

Two-sample t test power calculation

n = 52100.88

delta = 50

sd = 1912

sig.level = 0.01

power = 0.95

alternative = two.sided

NOTE: n is number in *each* group

I need to remember to apply the 15% overhead for non-parametric statistics, and I prefer to round up to the nearest multiple of :

nsamples <- ceiling(1.15 * mixed.pw$n / 1000) * 1000

print(nsamples)

[1] 60000

I would like to test the Mann-Whitney test with, so I create two samples from the distribution:

mixed.s1 <- 1000 + rmixed(nsamples)

mixed.s2 <- 1050 + rmixed(nsamples)

df <- melt(data.frame(s1=mixed.s1, s2=mixed.s2))

colnames(df) <- c('sample', 'value')

ggplot(data=df, aes(x=value, color=sample)) + geom_density()

And apply the test to them:

mixed.w <- wilcox.test(x=mixed.s1, y=mixed.s2, conf.int=TRUE)

print(mixed.w)

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

data: mixed.s1 and mixed.s2

W = 1728600000, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-60.18539 -43.18903

sample estimates:

difference in location

-51.68857

That provides the answer I was expecting, the estimate for the difference in the location parameter () is fairly close to the true value of .

More than the Location Parameter

So far I have been using simple translations of the same distribution, the Mann-Whitnet U test is most powerful in that case. I want to demonstrate the limitations of the test when the two random variables differ by more than just a location parameter.

First I create some more complex distributions:

rcomplex <- function(n, scale=2000,

s1=0.2, l1=0, s2=0.2, l2=1.0, s3=0.2, l3=3.0) {

g1 <- l1 + rlnorm(0.75*n, sdlog=s1)

g2 <- l2 + rlnorm(0.20*n, sdlog=s2)

g3 <- l3 + rlnorm(0.05*n, sdlog=s3)

v <- scale * append(append(g1, g2), g3)

return(sample(v))

}

and use this function to generate two samples with very different parameters:

complex.s1 <- 950 + rcomplex(nsamples, scale=1500, l3=5.0)

complex.s2 <- 1000 + rcomplex(nsamples)

We can still run the Mann-Whitney U test:

complex.w <- wilcox.test(value ~ sample, data=df, conf.int=TRUE)

print(complex.w)

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

data: value by sample

W = 998860000, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-581.5053 -567.7730

sample estimates:

difference in location

-574.6352

R dutifully produces an estimate of the difference in location, because I asked for it, but not because it has any reasonable interpretation beyond “this is the median of the differences”. Looking at the cumulative histogram we can see that sometimes s1 is “faster” than s2, but the opposite is also true:

I also found it useful to plot the density of the differences:

This shows that while the Hodges-Lehmann estimator is negative, and significant, that is not the end of the story, many samples are higher.

I should be careful in how I interpret the results of the Mann-Whitney U test when the distributions differ by more than just a location parameter.

Appendix: Learning about the Hodges-Lehmann Estimator

Just like I did for the Mann-Whitney U test, I am going to use synthetic data to gain some intuition about how it works. I will try to test some of the better known estimators and see how they break down, and compare how Hodges-Lehmann works in those cases.

Comparing Hodges-Lehmann vs. Difference of Means

I will start with a mixed distribution that includes mostly data following a Lognormal distribution, but also includes some outliers. This is what I expect to find in benchmarks that have not controlled their execution environment very well:

routlier <- function(n, scale=2000,

s1=0.2, l1=0, s2=0.1, l2=1.0,

fraction=0.01) {

g1 <- l1 + rlnorm((1.0 - fraction)*n, sdlog=s1)

g2 <- l2 + rlnorm(fraction*n, sdlog=s2)

v <- scale * append(g1, g2)

return(sample(v))

}

o1 <- routlier(20000)

o2 <- routlier(20000, l2=10)

The bulk of these distributions Those two distributions appear fairly similar:

However their means are fairly different:

print(mean(o2) - mea2(o1))

[1] 27.27925

The median or the Hodges-Lehmann estimator produce a more intuitive result:

print(median(o2) - median(o1))

print(HodgesLehmann(o1, o2))

[1] 1.984693

[1] 1.973359

I think this is a good time to point out that the Hodges-Lehmann estimator of two samples is not the same as the difference of the Hodges-Lehmann estimator of each sample:

print(HodgesLehmann(o2) - HodgesLehmann(o1))

[1] -2.908595

Basically Hodges-Lehmann for one sample is the median of averages between pairs from the sample. For two samples it is the median of the differences.

Comparing Hodges-Lehmann vs. the Difference of Medians

As I suspected, the difference of means is not a great estimator of effect, it is not robust against outliers. What about the difference of the medians? Seems to work fine in the previous case.

The example that gave me the most insight into why the median is not as good as I thought is this:

o3 <- routlier(20000, l2=2.0, fraction=0.49)

o4 <- routlier(20000, l2=4.0, fraction=0.49)

The median of both is very similar, in fact o3 seems to have a worse median:

print(median(o3) - median(o4))

[1] 11.32098

But clearly o3 has better performance. Unfortunately the median cannot detect that, the same thing that makes it robust against outliers makes it insensitive to changes in the top 50% of the data. One might be tempted to use the mean instead, but we already know that the problems are there.

The Hodges-Lehmann estimator readily detects the improvement:

print(HodgesLehmann(o3, o4))

[1] -1020.568

I cannot claim that the Hodges-Lehmann estimator will work well in all cases. But I think it offers a nice combination of being robust against outliers, while sensitive to improvements in only part of the population. The definition is a bit hard to get used to, but it matches what I think it is interesting in a benchmark: if I run with approach A vs. approach B, will be A faster than B most of the time? And if so, by how much?

Notes

The data for this post was generated using the driver script for the order book benchmark, with the e444f0f072c1e705d932f1c2173e8c39f7aeb663 version of JayBeams. The data thus generated was processed with a small R script to perform the statistical analysis and generate the graphs shown in this post. The R script as well as the data used here are available for download.

Metadata about the tests, including platform details can be found in comments embedded with the data file. The highlights of that metadata is reproduced here:

- CPU: AMD A8-3870 CPU @ 3.0Ghz

- Memory: 16GiB DDR3 @ 1333 Mhz, in 4 DIMMs.

- Operating System: Linux (Fedora 23, 4.8.13-100.fc23.x86_64)

- C Library: glibc 2.22

- C++ Library: libstdc++-5.3.1-6.fc23.x86_64

- Compiler: gcc 5.3.1 20160406

- Compiler Options: -O3 -Wall -Wno-deprecated-declarations

The data and graphs in the Appendix is randomly generated, the reader will not get the same results I did when executing the script to generate those graphs.